Tribal preservation officer wants to empower a new generation

Written by

Margaret SmithWorcester Magazine

August 13th, 2025

Andre R. Gaines-Roberson has been a traveling a path to understand his people, and himself. The Hassanamisco Tribe of the Nipmuc Nation, headquartered in South Grafton, recently announced Gaines-Roberson as tribal historic preservation officer. In this role, Gaines-Roberson's duties include overseeing all tribal historic preservation activities; ensuring cultural heritage protection, and reviewing federal and state projects under the National Historic Preservation Act.

But more than maintaining records and overseeing the proper location and care of artifacts, the role means protection and preservation of indigenous culture for the next generation, and preserving the wisdom and collective memory of elders and past generations.

It means traveling among and fostering dialogue with other indigenous peoples, and working with museums, natural history collections, and other organizations to ensure the proper care and location of the remains of indigenous peoples, sometimes taken unlawfully from burial places.

Gaines-Roberson has been working with the Museum of Worcester and the Mashantucket Pequot Museum, among other historical, scientific and educational institutions, on a range of work that includes exhibits, preservation and the respectful care of artifacts.

As much as his role is about preserving the past, it's about forging a path for the future.

Gaines-Roberson is also creative director of No Loose Braids, a Nipmuc-led organization working to bring eastern Woodland Tribal communities together, including through revitalization of traditional practices.

Gaines-Roberson marks 17 years of recovery from alcohol and substance use, and serves as a recovery coach with organizations such as MOAR, Massachusetts Organization for Addiction Recovery. In this work, he sees a mission: "To help others in this work of bringing balance to our people."

The Central Massachusetts region is sometimes referred to by indigenous peoples as Ground Zero, for the catastrophic effect of white settlers some four centuries ago, including violence, disease, displacement, and loss of traditional language and culture. "We come from a tribe in Grafton that has a reservation. It's only four and a half acres big, and a population of about 2,000 folks," Gaines-Roberson said. "The importance of us, being in our spaces, speaking for our ancestors and their remains, and speaking for ourselves is highly important, and I take that seriously."

What does your new position entail?

Well, a TIPO, also known as a tribal historical preservation officer, basically, it's preserving our ancestral remains and artifacts, and making sure that our remains and our ancestral artifacts are being handled in a proper way. It's a little difficult, with our tribe being a state-recognized tribe. We've been here since time immemorial. Not being recognized as a federal tribe, rules and regulations that deem certain folks in regards to certain artifacts and remains, and reporting back to our council , being in a good standing relationship. A good, collective manner, in a good way.

It's about actually going to collect and gathering; also, protecting sacred sites as well. I do a lot of land stewardship as well ... with the Department of Conservation and Recreation, Mass Audubon. A lot of management comes to cultural stewardship within the forest. We find a lot of things in the forest, as well as preserving particular sites, and route trails.

What brought you to this role?

It becomes a particular role within our community. We see people within the community for what they do, and what their walk is. The community has been seeing the work I do, besides the cultural work, finding historical artifacts ... I had that interest, and I believe the community saw it was a proper fit ... it's in my spirt and my heart, to take care of the spirits of our ancestors, in a good way.

When you were growing up, what and how did you learn about your culture?

I actually grew up on the Cape, and moved toward the South Shore, and then to my traditional territory in Worcester. Growing up, I heard and learned a lot from the Wampanoag folks, going to powwows since I was a little boy, engaged my relationship with my elders: my great aunt, and my dad. It was illegal until 1978 to have our ceremonies and our way of life (protected by law since Aug. 11, 1978, with the American Indian Religious Freedom Act.) It's no surprise that our language was diminished here, in Ground Zero. No matter where your travel in quote-unquote Indian Country, this is Ground Zero.

(The region now part of Worcester County was the location of so-called King Philip's War, 1675 to 1678, a bloody, armed conflict that saw massive loss of life among both native peoples and settlers of European origin. The slaying of Metacomet, the Wampanoag leader on Aug. 12, 1676, came to symbolize the catastrophic effect on native peoples in the region.)

When I was able to walk my path, my red path, this was 18 years ago, and I've continued to walk this walk.

What are some of the places your path has brought you?

I travel all across the country. I spend time every year in South Dakota ... going over there, and seeing what they have. When you look at the acreage, and looking at the language schools and emerging schools, and house, we don't even have housing. We are trying to create places for people to be housed ... that question, right there, is a deep, seriously important question when it comes to people who live here now.

The Masphee Wampanoag (which gained federal recognition in 2007,) is 20 years ahead of us ... as we continue to unite, and bring our collective ideas together, going to other people, it's an exchange of ideas, as an example.

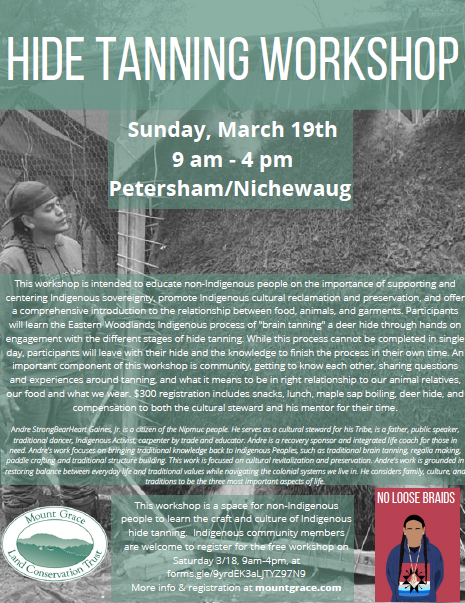

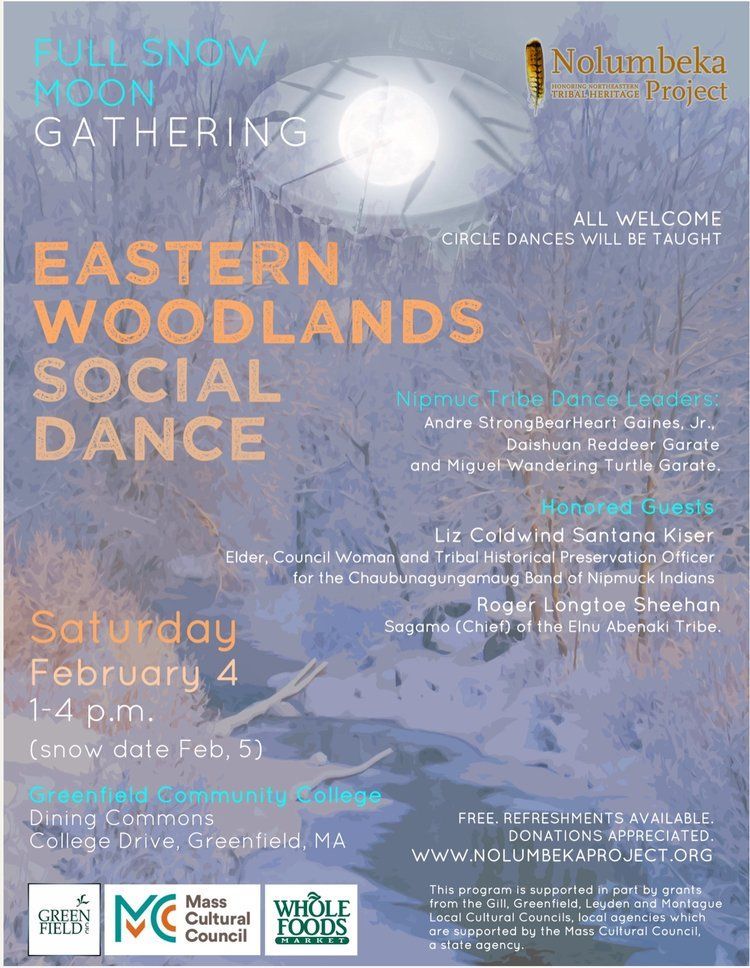

Some of the work we do here, our workshops, building dugout canoes, even making hand drums or something like that, or buckskin, we have what we call cultural exchange. When I travel to, say, South Dakota, to the Marty Indian School, (I show them) how to tan skins again, get them to actually tan a hide. I work with the school ... and then when I return, people hold space for us, space from the nonprofit Tiyospaye, they hold space for us to come. I headed over to the Lumbee reservation (in present-day North Carolina, and known as "people of the dark water,") they have large cedars. Doing our stewardship work, they are able to share different avenues with their canoes. We are both "paddle communities" (using waterways as a means of travel and transport.)

In the news, there has been controversy recently, about whether a person has claimed tribal affiliation authentically, such as allegations against (folk singer) Buffy Sainte-Marie. At the same time, this could create skepticism for people who genuinely identify indigenous ancestry or culture, being subjected to being told, "Well, prove it." Does this have an effect on the work you do?

I will say that in doing this work, if there are people who should not be in those places, that should be spoken about, because dealing with our ancestors' remains, our artifacts, what and who our community is, and what it means for the next generation, it's pretty important. And if people have challenges, they should bring it up, and bring it in front of people.

There are people who live in the city, who are not enrolled ... they are the very people who do the work we do in every way. That doesn't mean they are less Nipmuc, they just have a different path. I know who my family is. We have seven generations of genealogy. If people have this question, in this way, we can direct them to the council, and their records.

I hear you. It's an important issue to talk about it, but it's not going to stop us.

We were talking about how the work you do will impact seven generations. What do you teach the next generation about what their impact will be on the future?

I've already seen the work help the youth, help I didn't have ... we also live in a particular society now, where we need each other more, now more than ever. It's really important that people understand that. The work we are doing has very little to do with the lifetime we are living in now. We are setting up so my nieces and nephews. We just came out of a 400-year fracture. They save you have got to walk 20 years in the wood, and 20 years out.

Their responsibility to have cultural knowledge, it needs to be shared in a good way, so people don't feel ostracized, in trying to learn who we are. What society created was crabs in a bucket, divide and conquer. So, it's going to take us all to show a little love, and show the next generation, it's OK.